Reviewed by Rachel Wifall

“Sting Goes Renaissance”

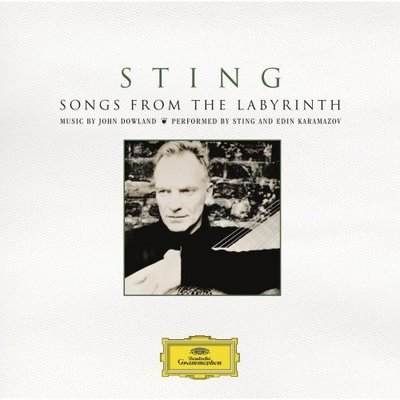

In Songs From The Labyrinth, Sting and Bosnian lutenist Edin Karamazov pay homage to the English Renaissance musician and composer John Dowland. Upon release in October, the album entered the UK Official Top 75 Albums Chart at number 24 and The Billboard 200 at number 37, rising the following week to number 25. It debuted at #1 on Billboard's Traditional Classical Chart and Classical Overall Chart, where it has remained for thirteen weeks.

Fifteen of the album’s sixteen songs were composed and originally performed on the lute by Dowland, a court musician in the late 16th and early 17th centuries; one (“Have you seen the bright lily grow”) was composed by Dowland’s younger contemporary, Robert Johnson, to lyrics written by playwright and poet Ben Jonson. Interspersed among the songs are readings from a letter which Dowland wrote to Sir Robert Cecil, Secretary of State and spymaster to Queen Elizabeth I, in 1595; in this letter Dowland defends his career choices, which took him to serve foreign patrons, and offers intelligence on possible foes to the queen, including his allegation that “men say that the Kinge of Spain is making gret preparation to com for England this next somer.”

Dowland went to Paris in 1580, where he served the ambassador to the French court. During this time he became a Roman Catholic, which conversion he claimed kept him from a post in Elizabeth I's fiercely Protestant court. In his letter he confides that he “gest that my relygion was my hinderance. Whearupon, my mynde being trobled, I desired to get beyond the seas”; after going abroad, Dowland worked instead for many years at the court of Christian IV of Denmark. After returning to England in 1606 he finally secured a post as one of James I's lutenists, in 1612.

Many of Dowland’s songs display the Renaissance vogue for melancholy; Sting relates to this, claiming that Dowland was “perhaps the first example of an archetype with which we have become familiar, that of the alienated singer-songwriter—something that gives him an acutely modern resonance.” Some of his tunes are upbeat, such as “Fine Knacks for Ladies,” which abounds in alliteration, metaphor and wit as it contrasts shallow materialism with amorous constancy: “Great gifts are guiles and look for gifts again./My trifles come as treasures from my mind./It is a precious jewel to be plain./Sometimes in shell the orient’s pearls we find.” However, even Dowland’s more uplifting love songs have a shadowy side: his famous rollicking “Come again” is an appeal a courtly lover makes to his mistress, full of sexual innuendo (“To see, to hear, to touch, to kiss, to die,/with thee again in sweetest sympathy”—“to die” metaphorical at this time for orgasm). While the original song encompasses six stanzas, Sting chooses to cut it off in the middle of the fourth, ending the number abruptly, yet effectively, on a decidedly lamenting note: “All the night, my sleeps are full of dreams,/My eyes are full of streams, my heart takes no delight.”

Edin Karamazov is one of Europe’s foremost lutenists, whose expertise is evident in his skilled and feeling interpretations of these complex works. Sting, who is studying the lute under Karamazov’s tutelage, plays briefly on track 15, after reading an excerpt of Dowland’s letter “…And from thence I had great desire to see Italy,” and in a duet with Karamazov (“My Lord Willoughby’s Welcome Home”). While on his website Sting claims “I'm not a trained singer for this repertoire,” the 16-time Grammy winner also says, “but I'm hoping that I can bring some freshness to these songs that perhaps a more experienced singer wouldn't give. For me they are pop songs written around 1600 and I relate to them in that way: beautiful melodies, fantastic lyrics, and great accompaniments.” While Sting has never displayed a great vocal range, his distinctive raspy and plaintive voice and his straightforward renditions are appropriate to this genre, rendering fresh and heartfelt Elizabethan and Jacobean popular music.

The name of the album comes from Sting’s fascination with labyrinths, a pattern of which is carved into the center of the soundboard of a lute which was given to him as a gift; in his informative and reflective introduction to the album, Sting also writes of his garden labyrinth, in which he and Karamazov became acquainted. He further relates the image of the labyrinth to his fascination with Dowland’s music:

Related to the Arabic ‘ud, the lute is close enough to the guitar for a modern guitarist to feel relatively familiar with it, but different enough in tuning and fingering to force a brain-teasing restructuring of synapses. Slowly and surely, I began to be drawn into the labyrinthine complexities of this ancient instrument and its beguiling music.

Sting and Karamazov have recorded a program entitled Sting: Songs From the Labyrinth, which was filmed at Sting's 16th-century manor house in Wiltshire, in the ancient gardens of Il Palagio (his home in Italy), and before a live audience at St. Luke's Church in London. It will air on Monday, February 26 at 10 p.m. (ET) on PBS Channel Thirteen/WNET. This Great Performances program will also be released as part of a special DVD/CD package entitled The Journey & the Labyrinth: The Music of John Dowland. Sting and Karamazov have also announced a European tour, which will begin in February. Tour dates are available at www.sting.com/news/index.php.

Digg This

Del.icio.us

No comments:

Post a Comment