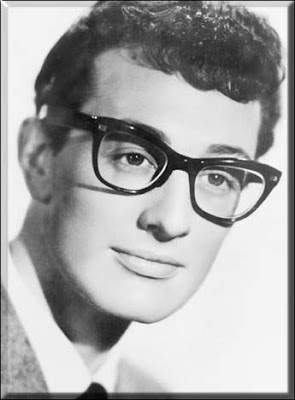

By the beginning of 1959, Buddy Holly had reached a crossroads in his career. 1957 had been a very successful year for him and his backing band The Crickets, with songs like "That'll Be the Day" and "Peggy Sue" cracking the top 5. Holly was no less productive or creative in 1958, but for some reason the luster had started to wear off. The acoustic ballad "Well.. All Right," for example, would eventually be regarded as a classic, but it fell through the cracks when it was released as a single in November. It would prove to be the last single Holly would record with the Crickets; Holly relocated to Greenwich Village in New York City with his wife. January 1959 saw the release of a solo single "It Doesn't Matter Anymore." Just as "Well... All Right" foreshadowed folk rock by several years, the orchestrated accompaniment of "It Doesn't Matter Anymore" would not be duplicated by any rock artists until the second half of the next decade. By this time, Holly had been offered the headlining spot on a three week tour of the Midwest called the Winter Dance Party. Although his wife had just become pregnant, Holly decided that he needed to go, and recruited Tommy Allsup (lead guitar), Waylon Jennings (bass), and Carl Bunch (drums) to back him up.

California teen sensation Ritchie Valens was unquestionably a rising star. Only eight months into his recording career, Valens had already scored hits with "Come on Let's Go" and the classic double A-side "Donna/La Bamba." Valens' use of ethnic folk music and the Spanish language in a rock context on "La Bamba" was unprecedented, and the rapid acceptance of a Latino peformer by rock audiences would not be duplicated for a full decade.

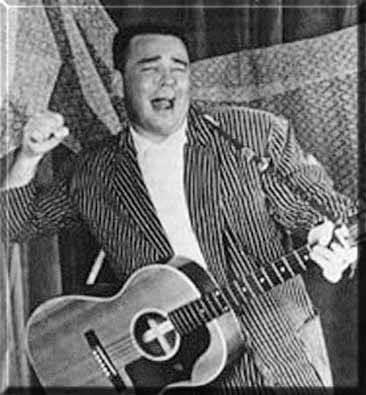

Much like Holly's bandmate Waylon Jennings, J. P. Richardson was a popular disc jockey before he became a professional musician. Whether singing or DJing, though, he was known by his nickname "The Big Bopper." Richardson's radio experience gave him a keen understanding of how music promotion and publicity worked, and he figured out that TV was a resource that wasn't being fully tapped by other artists. His televised performances of his biggest hit "Chantilly Lace" were quite theatrical, with Richardson talking the lyrics of the song while on the telephone. Perhaps most significantly, he is credited with coining the term "music video," and he certainly intended to pursue the idea further if he got the chance. Like Holly, Richardson left his pregnant wife behind when he embarked on the tour.

Along with Holly, Valens, and Richardson, the Winter Dance Party line-up was completed by the Bronx doo-wop group Dion and the Belmonts. Holly's band would back up each performer. The tour commenced in late January, and things started to go wrong almost immediately. The tour bus broke down repeatedly, and even when it did work, its heater did not. To add insult to injury, the temperatures in the bitter Midwest winter frequently dropped below zero. While Dion recalls with fondness the long nights spent jamming with Holly and Valens on the back of the bus, the traveling conditions started to wear on Holly. Things got even worse for the tour when Carl Bunch got frostbite on his feet; one of the Belmonts was a competent drummer, and had to take his place.

The tour reached the town of Clear Lake, Iowa on February 2. Clear Lake had an airfield nearby, from which planes could be chartered. Believing that a quick flight to the next tour stop and a decent sleep in a warm bed would do him much good, Holly chartered a plane for after the show and tried to talk the other headliners into going in on it with him. Dion balked at the price of $36 per person. His parents always fought over money when he was growing up, and $36 just happened to be the cost of one month's rent for their apartment. He simply couldn't rationalize spending a month's rent on a 45-minute flight. Holly was intent at this point to give the other two seats on the plane to Jennings and Allsup, but fate intervened. Richardson had a bad cold, and Jennings graciously obliged him when he asked for Jennings' seat on the plane. Valens, also suffering from a cold, begged Allsup to give him his seat as they were packing up after the show. Allsup offered to flip a coin for it. He lost. As the bus was getting ready to move on, Holly started joking with Jennings. "Well I hope you freeze to death on the bus," he told him. "And I hope your plane crashes," Jennings said in reply.

At approximately 1 AM on the morning of February 3, 1959, the plane carrying Holly, Valens, and The Big Bopper took off. It stayed in the air for no more than five minutes. Richardson was 29, Holly 22, and Valens only 17.

The events of that night, and the performers involved, have had an effect on popular culture that lingers on fifty years later. The most obvious example is Don McLean's extremely popular 1971 song "American Pie." The song chronicles the loss of innocence of rock and roll and youth culture, using the crash as its starting point and going through the sixties. Buddy Holly's music is undeniably great in hindsight, even if the chart success had already dried up for him. Kids in America may have stopped paying attention to him, but certain kids on the other side of the Atlantic hadn't. You could argue that no 50's musician, not even Elvis, influenced the British Invasion more than Buddy Holly did. The fact that The Beatles and The Rolling Stones both happily cited him as a primary inspiration speaks for itself, and there was even a group called The Hollies who named themselves after him. Ritchie Valens opened the door for Latino performers in much the same way that Jackie Robinson opened the door for black baseball players. His legacy can be heard in the music of bands like Santana and Los Lobos (even without the obvious movie connection). While The Big Bopper has never been deemed worthy of a major motion picture about his life, he too was a musical pioneer in some significant ways.

Indeed all three performers were ahead of their time, and still pushing the barriers when they died. Rock music has had far too many tragic days, but only the murder of John Lennon rivals this crash in the way it has moved those who love the music. Lennon at least had the time to realize his full potential as a performer, though. Holly was expanding his musical horizons faster than his audience could keep up with him, and had relocated to a place that would become one of the hotspots for musical creativity in the coming decade. The sixties would vindicate everything that Holly was trying to do, but he never lived to see it. Valens was just starting, and had shown much promise while being so young. Unfortunately, we can only speculate on how much music we lost that night.

Ultimately, though, the events of February 3, 1959 are worth acknowledging because Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J. P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson deserve to be remembered. All three had accomplished much in a short time, and all three shaped the course that rock music would follow long after they were gone. They each left an indelible imprint on music in ways that no tragedy can dim.

No comments:

Post a Comment